Coloring the Universe: How Beautiful Astronomical Images are Made

Astronomers have made discoveries that have completely

changed our view of the Universe and our place in it. Their advanced telescopes

have given us a kind of superhuman vision that greatly surpasses what our eyes are capable of in terms of

sensitivity, resolving power and wavelength coverage. Their spectacular images rival

the beauty of our finest works of art.

The technology and expertise required to obtain these images

is just as impressive as their beauty. The book “Coloring the Universe: An Insider's Look at

Making Spectacular Images of Space”, released in November last year,

gives perhaps the best description available of how these beautiful images are

obtained, ranging from a description of the instruments used, to the software

techniques adopted to produce the best presentations. Travis Rector, Kim Arcand

and Megan Watzke wrote

the book. Travis Rector, an astronomer

and one of the world’s best at producing astronomical images, wrote a seminal paper giving a

“practical guide” on “how to generate astronomical images from research data

with powerful image-processing programs”. Kim Arcand and Megan Watzke are both award-winning

science communicators and authors, with extensive experience in disseminating

images to a global audience. (In full disclosure, Arcand and Watzke are Chandra X-ray Center colleagues and friends

of mine, and I also reviewed

a previous book by them, called "Your Ticket to the

Universe". In between they’ve written a book called “Light” that

is full of gorgeous images from many fields of science.)

|

| Figure 1: The cover of Coloring the Universe, showing an optical image from the NSF’s Mayall 4-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory of IC 1396A, a dark nebula more commonly known as the Elephant Trunk Nebula. Credit: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage) and H. Schweiker (WIYN and NOAO/AURA/NSF). |

The text in Coloring the Universe is eloquent and accessible to a wide audience. The book has excellent organization, and each chapter is broken up into easily digestible subsections. Some of the topics covered include a comparison of human vision with telescopic vision and a discussion of what astrophysics can be learned from images. It also explains some details about observing at the world’s largest telescopes and discusses the different kinds of light that we observe.

As expected, the book is full of spectacular images, many

produced by Travis Rector and his colleagues, with careful descriptions given

in figure captions. It’s striking that many of the ground-based telescope

images by Rector et al. are just as beautiful as those made by NASA’s Hubble

Space Telescope (HST). For example, here is a HST

image showing part of the Veil Nebula, the remains of a supernova in our

galaxy:

|

| Figure 2: An HST image showing part of the Cygnus Loop supernova remnant, the expanding remains of a massive star that exploded about 8,000 years ago. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) |

For comparison, here is a ground-based image from a different part of the remnant:

|

| Figure 3: An optical image from the Mayall 4-meter telescope, of the region known as Pickering's Triangle, also part of the Cygnus Loop supernova remnant. This image is rotated by 180 degrees from the one used in the book. Credit: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage) and H. Schweiker (WIYN and NOAO/AURA/NSF). |

In this case and many others, the much bigger field of view of ground-based telescopes compared to HST can compensate for their much lower spatial resolution, as I described in a blog post in 2014: “What Makes an Astronomical Image Beautiful?”, based on a paper by Lars Lindberg Christensen and colleagues. One reason that HST images are often more familiar is that they have a more powerful publicity engine promoting them. Coloring the Universe allows part of this publicity imbalance to be rectified.

|

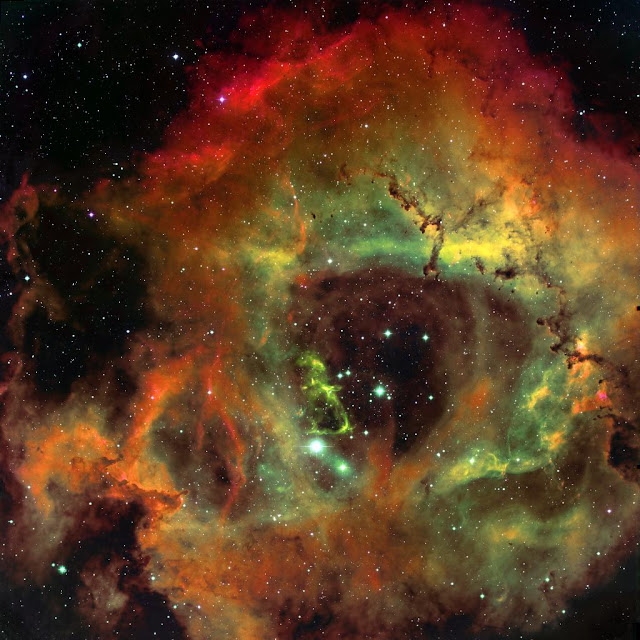

Figure 4: An optical image using the NSF's 0.9-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory of the Rosette Nebula. Credit: T.A. Rector, B.A. Wolpa & M. Hanna (NOAO/AURA/NSF).

|

Criticism of

astronomical images

Two motivations for writing Coloring the Universe are to demystify the production of

astronomical images and indirectly respond to critics. For publicity, beautiful

images give astronomy a clear advantage over many other fields of science, as

we have found in publicizing Chandra results. There doesn't have to be exciting

or important science for a particular result to receive widespread attention.

However, not everyone can appreciate such beauty without deep skepticism, and over

the years I’ve collected some critiques of astronomical images. (I forgive but

I don’t want to forget.) For example, in a New

York Times review of an exhibition of solar system images, the writer

described the “sub-wooferish whooshes of sound” accompanying planetarium shows

using HST images. He followed by writing “Well, the colors are as phony as the

sound.” In another example, science writer Charlie Petit described HST images as

being “simultaneously dreadfully misleading, worthwhile, and useful”, in one

post at the Knight Science Journalism Tracker (now archived at the online

magazine Undark). Referring to the famous HST

image of the “Pillars

of Creation” in a

2007 post, Petit said “The Tracker finds it worth posting in part just to

put up the Hubble telescope’s unbelievable image from ten years ago

(unbelievable is literally true. Its power came from extensive color tweaking

that gives it far more drama than would greet the naked eye).”

It’s not just writers who have been critical. Washington

Post writer Joel

Achenbach wrote about

the mostly negative reactions of astronomers to the Pillars of Creation

image (scroll down to the text “From a 1997 story I did in the magazine”). The

astronomers criticized the colors used and they also criticized the orientation

of the image, as though it’s important for a public audience to maintain the

arbitrary astronomer’s convention of North pointing up. These comments were

collected almost 20 years and hopefully since then astronomers have gained a

better appreciation for the optimal presentation of images for a public

audience. I’m not sure this is the case, and for what it’s worth, a 2015

study by Kim Arcand and colleagues of what people think is “real” in astronomical

images showed no significant difference between the opinions of self-rated

experts and non-experts.

Critics like those described above would gain a better

understanding of how images are made and the motivations behind these methods

by reading Coloring the Universe. For

example, the book contains a chapter called “Photoshopping the Universe: what

do astronomers do? What do astronomers not do?” followed by a chapter called “The

aesthetics of astrophysics: principles of composition applied to the Universe”.

The latter includes a fascinating subsection on why the Pillars of Creation

image looks so dramatic.

Responding to the

criticism

As Kim

Arcand and colleagues explain in discussing the aesthetics of images, the

use of color leads to the most questions and comments. As noted earlier, this

can result in claims that astronomical images are faked & that they're

nothing like what the eye would see. My response to the former is “no!” and my

response to the latter is: “why should they be, when telescopes can see so much

better than our eyes?” It’s a common fallacy to assume that astronomical images

are meant to show what our eyes can see, or might be able to if they were more

sensitive. Astronomical images can convey an enormous amount of information,

especially when they are not limited by the shortcomings of human vision. For

example, images can show narrowband, optical images to pick out phenomena that

our eyes are unable to discern. Even more significantly, they can show objects and

phenomena in wavelengths that are well beyond the range of human vision, such

as X-rays and radio waves.

|

Figure 5: A composite image of NGC 602, a cluster of bright young stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a nearby galaxy. Chandra data is shown in purple, optical data from HST is shown in red, green and blue and infrared data from the Spitzer Space Telescope is shown in red. Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ.Potsdam/L.Oskinova et al; Optical: NASA/STScI; Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech

|

As various image experts have explained over the years, such as Megan Watzke, Kim Arcand and Robert Hurt, the colors used in astronomical images are often representative, which means that they are not intended to show how our eyes might see the object, but instead represent maps of the electromagnetic radiation produced at different wavelengths, and with a range of filters. Astronomers often use the term “false color”, but that terminology is misleading for non-expert audiences, as Robert Hurt and others have pointed out. In many cases images simulate what our eyes might see if they were sensitive to very different wavelengths, like Geordi La Forge's visor-enhanced vision in Star Trek the Next Generation.

A good example in Coloring

the Universe is the Chandra image of Tycho’s supernova remnant, the remains

of a supernova seen on Earth in 1572. Here, the shortest wavelengths are shown

in blue, intermediate wavelengths are shown in green and the longest

wavelengths are shown in red, in the same order and wavelength order as our

vision at optical wavelengths. This use of color helps explain the

astrophysics, as the outer blast wave has produced a rapidly moving shell of

extremely high-energy electrons (blue), and the supernova debris has been heated

to millions of degrees (red and green).

|

Figure 6: A Chandra image of Tycho’s supernova remnant. Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO

|

Coloring the Universe

gives a much more detailed discussion of the meaning and value of

multiwavelength images, and the use of color in making attractive images that give insight into their scientific content.

Without giving too much away, here are a few other highlights

of the book:

- It shows a sense of humor, e.g. in describing how colors should be used appropriately it notes that people in images wouldn’t be colored green “unless you’re in Roswell, New Mexico”. Also, since optical astronomers observe (hopefully) all night, the authors note, “like vampires we sleep during the day” and “Fortunately, we don’t sleep in coffins”.

- I liked the use of raw images to show what telescopes collect before processing has been done, and how calibration and multiple exposures correct for changes in charge coupled detector (CCD) sensitivity and gaps between CCDs.

- It gives an excellent description of the history of astronomical images and their dissemination, including HST’s observations of Jupiter and Shoemaker-Levy in 1994 at a pivotal time for the production and dissemination of images. The World Wide Web started in 1991 but its use was limited until the Mosaic web browser was introduced in 1993. Another big step was the release of layering capabilities in Photoshop in 1994, allowing sophisticated color composite images to be created.

- An authoritative description is provided of the important role that images play in publicity, including the establishment of programs like Hubble Heritage, providing the opportunity to gather beautiful images that professional astronomers might have missed.

“In this book we’ve talked about

the complex process of converting what the telescope can see into something we

humans can see. It’s a fundamental challenge because our telescopes observe

objects that, with a few exceptions, are invisible to our eyes. That is of

course the reason why we build telescopes. There would be no point in building

machines like Gemini, HST and Chandra if they didn’t expand our vision.

Astronomers use telescopes to study and understand the fundamental questions of

how we came to be: from the formation and fate of the Universe; to the

generation and function of galaxies; to the birth, life and death of stars

inside galaxies; to the planets and moons around these stars; and to the origin

of life here and possibly on worlds beyond our own.”

The text continues with an eloquent summary of the

principles and motivation behind the production of astronomical images, which

you’ll have to purchase

the book to enjoy. I highly recommend that you do so, to savor the gorgeous

images Coloring the Universe contains

and to appreciate the ingenuity involved in producing these images.

End note: While waiting for Coloring the Universe to arrive in the post, you can watch this excellent

talk by Jayanne English

from the University of Manitoba, titled “Are images of space realistic?”

The universe is surely a mesmerizing thing. The beauty is holds the vastness it has is truly mind-boggling. Thanks for posting this, it amounted for a great read. Love it.

ReplyDelete